![]() hand. main. دي . 手. tangan. panangan.

hand. main. دي . 手. tangan. panangan.

Click, hold, press, push, swipe, tap, touch. Hands have become the medium that mediates and “massages” our ways of sensing, feeling, thinking, seeing, and being in the world. In and of our hands, analogue and digital techniques compute the real and the symbolic; they construct, reconstruct, imagine, and reimagine our many social worlds. Using hands as a focal point, “Hands: Medium & Massage” attempts to visualize, conceive, encode, and recode our ambiguous and complex relationship with the immaterial and material world, everyday techno-social lives, and the hyper-mediated environment we inhabit. The series endeavours to create a moment and space for re-thinking the existence and roles of “hands” as “medium & massage”.

MENU

VIEW this website as SLIDESHOW

interested in getting your own ‘hands’?

Bio & Statement

The Artist

A prolific artist and compulsive doodler, Merlyna Lim loves to draw anytime, anywhere, in any medium. Self-taught, Merlyna began sketching and painting as a means of escaping the everyday reality of living in Dayeuhkolot (Bandung, Indonesia), an industrial, working-class, flood-prone district where she was born and raised.

Merlyna sees her work of art as a lens though which one can see, read, and feel how stories and memories are stored, preserved, told, and retold. She sketches and paints as a way of locking images and experiences in her memory as well as unravelling her own thoughts and expressing her own personal feelings and emotions. Through her work, Merlyna wishes to bring narratives of moments, events, and phenomena closer to the audience, while giving them space to insert their own interpretations.

Noted for its contradictions—expressive yet restrained, simple yet complex, dark yet hopeful—Merlyna’s work embodies a relentless pursuit for the most basic and instinctive way to visualize ideas, phenomena, and stories of “us” and the world we live in. She enjoys working in multiple media—from pencil to ink and watercolour to oil on canvas—as each different medium allows her to express ideas differently.

Having lived in Indonesia, the Netherlands, and the United States, Merlyna currently resides in Ottawa, Canada. A singer and instrumentalist, in her spare time, she likes to sleep, daydream, walk, cook, and play music. When not doodling, Merlyna enjoys writing, researching, and teaching in her capacity as Canada Research Chair in Digital Media and Global Network Society, Associate Professor of Communication and Media Studies, and a founder and director of the ALiGN Media Lab at Carleton University.

An award-winning scholar and artist, Merlyna Lim was named a member of the Royal Society of Canada’s New College of Scholars, Artists, and Scientists in 2016 and the 1st winner of 2017 Jackson’s Art International Urban Sketching Competition (People’s Choice Award).

Foreword

The Hand

Technology is the realm of the hand. We often forget this, spending most of our time considering technology in terms of brains, eyes and ears, or social relationships and cultural practices. But the hand is the first and primary interface between the human body and most technical objects. Access to modernity’s many media environments is granted only through the hand: tapping, clicking, turning, pressing, swiping, grasping, pulling, porting. Today there is no liking, sharing, retweeting, posting, or streaming without these humble techniques of the hand.

Our thinking about media and technology has long suffered from this omission. Even a perceptive thinker like Marshall McLuhan gave short shrift to the hand. In his considerations of the telephone, for instance, McLuhan attributed far more importance to the ear and mouth in the intimacies and uncanniness of the phone. Yet the hand was there all along, quietly supporting the sexier activities of its sensory siblings: grasping the receiver, tapping buttons, turning dials, plugging and unplugging cords. It is the forgotten third, the mediator of this media device; without the hand there is no telephone conversation.

Hands are about techniques, operations and the work of articulation. Anthropologists and philosophers have long considered the importance of the hand’s dexterity to the emergence of human civilization. To grasp, pull, or carry an object alters its position in space and time, opening it up to new possibilities and patterns of use, whether a bone or a stone, a plant or a phone. To take an object in the hand and transform it into a tool that can reshape the world around us is a kind of magic. Stanley Kubrick famously dramatized this in his “Dawn of Man” preface to 2001: A Space Odyssey. The sequence is unusually attentive to the hand but also grasps, in the eruption of violence it depicts, a Promethean tension: that hands are about craft, skill and ingenuity, yet also our most primal weapon and power technology. More powerful even than a fist that strikes an opponent is the hand that points, that communicates a difference, that selects one but not others. To be pointed at is so exhilarating and unnerving because one is never really sure what fate the gesture will bring: opportunity and stature, or punishment and exile.

As Merlyna Lim’s drawings brilliantly show, these deep logics of handedness remain with us. We have built a world that privileges and demands much of the hands that we otherwise take for granted. Such a world punishes hands that do not abide by the standards of normalcy that get designed into technical devices and networks. Just as the hard of hearing were, and are, excluded from the telephone’s ear ecology, the differently-handed are shut out from many ecologies of making, shaping, and using. Because of its connection to technique, the hand also teaches us about labour—not just in masculinized realms of making and tinkering, but in tasks historically feminized and undervalued: caring, supporting, maintaining and repairing. Hands of embrace, solidarity and care—cradling a head, stitching a tear, washing an exhausted body, fingers running through hair, taking your hand in mine—offer a powerful antithesis to hands that seek control, order, or dominance.

Such insights emerge when we consider the hand in all its technical, operational, interfacial, caring, and ambivalent possibilities. Merlyna Lim invites us, for a moment, to so focus our attention.

Touch of Tech

26 And Machine said, Let us make Humankind in our image, after our likeness: and let Them have dominion over the satellites and submarines, and over the drones of the air, and over the freeways and motorcars, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.

27 So Machine created Humankind in its own image, in the image of Machine created it Them.

28 And Machine blessed Them, and Machine said unto Them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replicate me: so that You might find comfort in relinquishing your own Creation.

…

Touch of Tech

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

24 in x 18 in

Dialectic

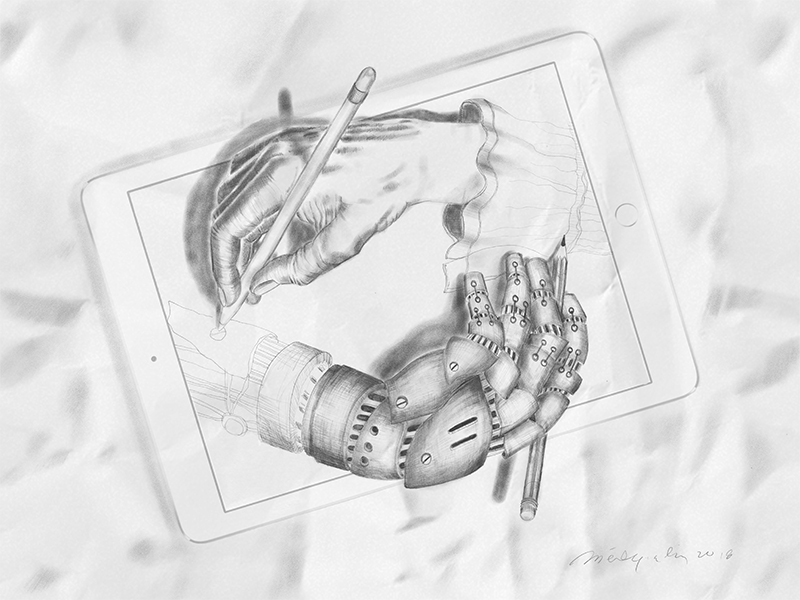

I recently read a definition of the term binary that made me pause. It made reference to two parts of a whole. This got me thinking about division and decision-making. Dividing a whole into two parts is just one decision of many. It may limit how well we can make sense of what is in front of us. Consider an avocado—today’s trendy toast topper. You can decide to cut an avocado exactly in half to create two symmetrical pieces. But if you cut it the way I’m accustomed, you’d still be left with the pit. Which side does the pit belong to? The initial binary logic reveals itself as asymmetrical. Let’s interpret this as a nudge to consider a different cut entirely. Moving from avocados to the hands depicted here, we can similarly choose to look beyond the binary of human and non-human. Dividing by two is inadequate anyways—perhaps even impossible given that humans create technology and technology shapes us in return. It is a mutual relationship and, as depicted here, a dependent one: both hands require the other to exist. If one hand were to jolt unpredictably, a ripple effect would jolt the alternate hand, leaving both constructions in disarray with unexpected lines protruding outside the anticipated frame. If we hedge our bets on a neat division between the two, we will fail. Instead, let’s envision a spectrum that makes up the whole; an intermingling of social and technical bits that forever evade simple binary division.

…

Dialectic

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

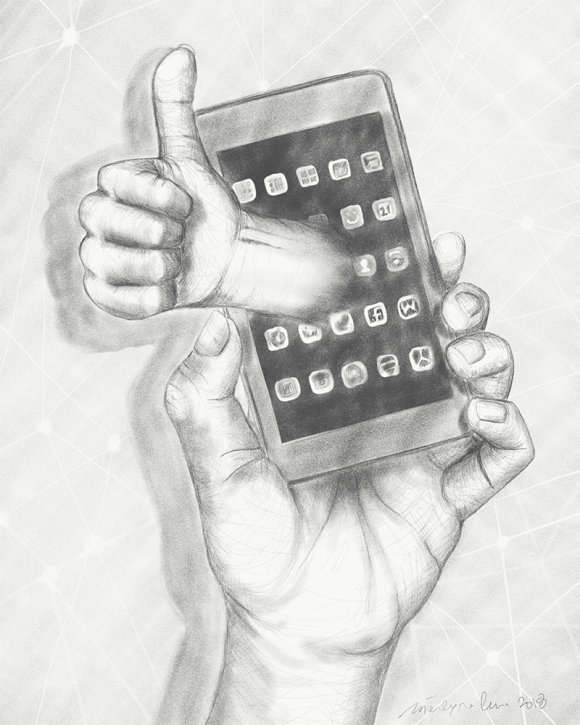

iPoison

One fine day.

Wake up in the morning. I immediately reach my cellphone.

Ding ding. WhatsApp’s messages are coming in. As well as notifications in my social media.

After taking a shower, I, again, reach my cellphone. Browsing information and chatting with friends. Until… OMG, time to go to the office. In a hurry, I prepare myself.

On the way to the office I, again, look at my cellphone screen. Besides reading what’s up in my social media timeline. This helps me avoid interacting with others.

In my office building, I look at my cellphone screen, again, to avoid chit-chatting with others.

Lunch time. Five of us are having lunch together. As soon as we order our food, everybody is busy with our cellphone. Sometimes we chat with each other, in writing through WhatsApp’s group for sure, not verbally.

On the way home, again, I am busy with the cellphone. Then it’s time to get off the bus. This time I’m cautious, because a friend of mine told me a story that she fell from the bus because she kept staring at her cellphone while stepping out of the bus.

Before bed, I, again, am busy with my cellphone: video calling a friend, browsing social media timeline, socializing in chat groups. Then I hear someone calling my name. Shocked, I open my eyes. Apparently, I fall asleep with a cellphone in my hand, and unconsciously call my friend.

One fine day?

…

iPoison

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

18 in x 24 in

Coded

coded in binary

1101 1000100100 110 100 11 011

these hands catch

cascades of vibrant matter

molecular and particular

entangled in becoming

amid essences of life

captured as code

we are all particles

clustered along conduits and wires

our pixels and bits

mingling desire and words

as amplified signals

that bring forth a world

you curate me

…

Coded

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

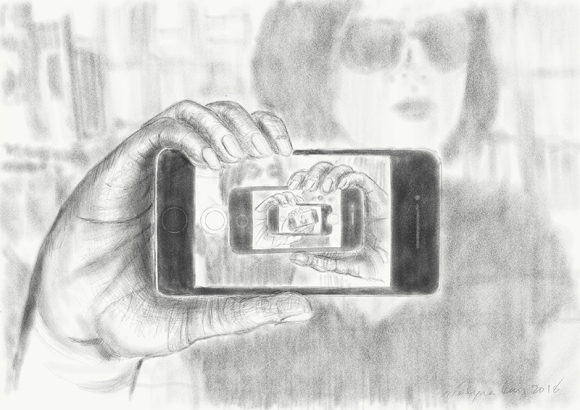

Selfie

…

Selfie

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

Convergence

Serenity

The prayer is familiar and familial:

Muttered under my mother’s breath.

Praying hands cross-stitched and framed next to crucifix.

Embossed on coins tasked with wearing out worries in pockets

Rubbed so flat it’s no longer legible

what God is being asked to grant.

What difference between courage and wisdom

there is to make.

It starts with Grandpére,

who still pulls his coin out at the dinner table.

His trophy for fifty years dry.

Not a drop, he says in thick Acadian,

smiling down at his Anglophone grandchildren

while the women side eye

over beer-battered haddock.

I get one as a graduation gift and

try to keep tradition.

But after three rounds of disappointing clangs in the dryer,

I put it away in a drawer.

I find it eight years later.

After the rupture.

The breaking apart of the hands to run them over

your curved thighs, your curly hair.

I press the letters against my thumb,

thinking of my mother’s new inversion:

I accept the things you cannot change.

She holds her faith in balance with this imagined rigidity.

As though I would find courage,

if only I could.

I bring it with me to the mountains.

The first morning I wake up in the bed you grew up in

the magpies squawk all morning.

You groan and roll over

but I understand their plight.

For sustenance, for space.

For coins like trophies.

Sacred, heart-rending, hidden away.

…

Convergence

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

18 in x 24 in

Hacked

Socially Hacked/Lateral Surveillance

You come in because I let you in—invading the privacy, that I just gave up. By design. By social pressure.

The private is political they say, but now the private is also monetized. The invisible algorithm penetrating into valuable spaces of intimacy: (When) Did I lose control and let you take over?

…

Hacked

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

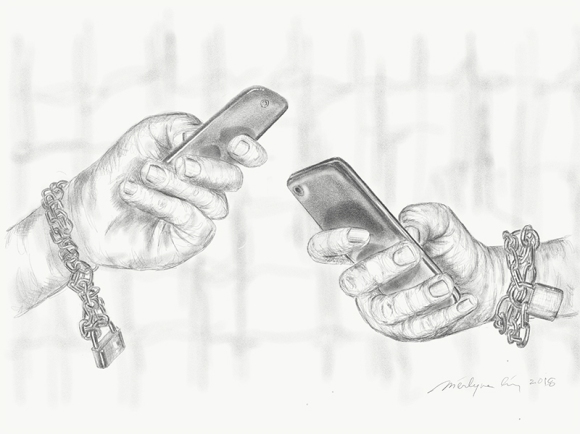

Chained

Longing to set oneself free

But your grip haunts me

Your inadvertent presence draws me into bottomless possibilities

Here I am, chained by technology

…

Chained

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

24 in x 18 in

Existences

Our being is one of deep relationality and hands-on co-existence. As we are brought into the world it is by labour assisted by hands. As we bring a world into being we rely upon those hands that preceded ours and that inscribed themselves into the fabric of the world. Even in digital existence, as these systems are at our fingertips, hands across keyboards and screens are there working to wield influence, to connect existences. The job was however always bigger and more wearisome than any super heroic individual deed, it was a mending of the world: Tikkun olam. We are thus thrown into the world with the assignment to care for and about our world and each other. This task to repair belongs to each of us individually, but was never in any singular pair of hands. And the question that remains today in relation to this human condition, will digital media systems of increased automation—including their message as media—come in handy for us? If not, why should we be handing ourselves over to them?

…

Existences

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

Datafied

Is this you?

Is this really you?

Roscher, Vucetich, Henry

Really, I know you?

Dactyloscopy

Friction, ridges and black ink

Biometric you/

It is the surface

Dermatoglyphication

Fragmentary you

Pliability

Deposition and slippage

Material you

Dusting, powdering

Sebaceous, aqueous remnants

Augmentating you

Digitization

Databases in the cloud

Bit and Bytes of you

Who really knows you?

Datafication, traces

Only parts of you.

…

Datafied

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

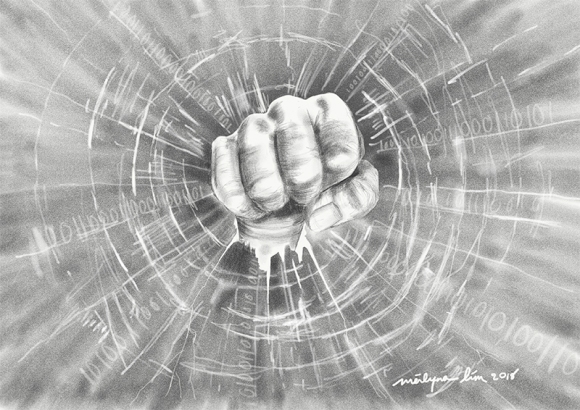

Resist

A closed fist presents an immediate threat—even a promise—of what will come if pushed. It yells ‘back up, back off, back down.’ Power. Physical action. Violence. I wish I lived in a world where force didn’t seem like the answer.

I think we forget that sometimes violence can be a necessity, and that non-violence is a luxury and privilege not afforded to everyone. Push me and I will push back. I will never turn the other cheek. Instead, I will lean into the use of violence.

Yet this fist comes with the title, ‘resist.’

Is it suggesting resistance through violence? Or does the subtle code that surrounds this angry fist suggest a more nuanced approach? Resist. Refrain. Repel. In other words, perhaps resisting violence and instead, rebel, challenge and disrupt through other means.

Could a world brimming with anger, ready to break out in violence, rebel through digital methods? Life isn’t binary. It isn’t yes, no. Good, bad. But maybe the building blocks of digital code have a place in how we can resist today.

Despite the hint of the violence to come, this fist also speaks to strength, courage, and breaking through barriers. A fist is just so personal.

It makes one wonder: what would it take to empower this fist to open?

…

Resist

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

Dis/Connection

Growing up, I lived in a working-class neighbourhood of Los Angeles, over 4200miles from my village in the Peruvian Andes. The journey home was made by flight, bus, and foot. There were no paved roads, no running water, sparing electricity, and I loved it. Returning to the U.S. always felt empty. I missed the warmth of my grandmother’s wool skirt, smell of her hair, the sun burning my cheeks, the feel of rich soil in the farm fields. But in the U.S., we drove our own car and watched television; we re-entered the trance of modernity. But there were tinny connections—calls to the one phone in the village. I can still hear my mother shouting above the static—“Raul, can you hear me?!” Wiring and copper. The cassette tapes that my progressive Uncle Antonio sent in the post contained music he had recorded during rituals—the sound of the tinya drum, shrill women’s singing, the cow horn, and shout-outs to dancers. Plastic and cobalt. My ancestors were ingenious. We Indigenous peoples say that, and we believe it. Had the Spanish not arrived, had other Europeans not followed, had the private and multinational corporations not done what they do, what would we have made? We calculated the distance from the earth to the moon, we built marvels of hydroengineering, we constructed stone structures that withstood earthquakes. We believed in something greater than ourselves. Maybe we still do. I’m not sure.

I’ll ask my uncles in our next video chat.

…

Dis/connection

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

24 in x 18 in

F**k

Cyborg

Artificial

Human

Nature

Binary that Binds

and Bites, like Reality

through the Bytes

Click to Enter: Domination

Should I enter?

The hand flickers

Which hand?

Whose hand?

The Signifier’s

The One who bites the hand that feeds…

Scrolling through the newsfeed

Anger

Frustration

Sadness

Illusion

Temptation

Just one more

Click

The Ad says

But I say,

F**k You.

…

F**k

2019

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

18 in x 24 in

Hegemony/CONTROL

Platform (a song)

I’ve got nothing to lose

Nothing to gain

You come from afar

You enter like rain

I’ve got no way to fight

Got no way to win

You offer relief

You offer me in

Let’s get something more fit

Let’s write; we’ll get into it

Let’s form something for all

Platform with open protocol

Back there

There’s nothing to choose

Back there, there’s nothing but you

I know

It’s not right but hey

If you’re not there,

There’s nothing to say

We could save all that up

We could take them all down

We could open the code

And carry the shout

That’s it

There’s more ways to live

Got to gain back control

Got to threaten to give

…

Hegemony/Control

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

18 in x 24 in

DEmoticonized

They figured out that there are exactly 43 emotional states, as assessed in terms of unique neurochemical signalling pathways. This is the universe of what we can feel, and now we can have an emoticon for each. This makes the shrink’s job easier; no more talk, just point to the chart and I’ve got just the thing for you. Major works are currently being translated; Ahab holding the lightening chains, and Medea her dead children, can be rendered with a single emoticon! Ditto Bambi and Mme. Bovary. To get some sense of what it all adds up to: Brands of breakfast cereal outnumber emotional states by about 14:1. (Not including countless artisanal granola brands.) Another way to think about it is that the number of emotional states that eating cereal can induce is a whole lot less than the total number of cereals. Based on this, I’m working on an app that groups all the cereals by emoticon. First I’ll have to map signalling pathways to each cereal, so I’m launching a Kickstarter campaign to fund the research.

Please consider contributing! 🙂

…

DEmoticonized

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

24 in x 18 in

..

…

Digital

Digits certainly compute, but they also do far more than that. Like fingers, they also point. And, as anyone who has been burned by a misplaced finger knows, pointing is far from an exact science. Just as the internal systems digital media compute are finite, rational, and discrete, so too must the external world to which the same media point remain infinite, irrational, and approximate, and it is this difference that firmly insures against both the promise and the threat of total digital convergence. Consider the longer view that emerges once we see digital media as those media that, like our fingers, count the symbolic, point to the real, and manipulate the social imaginary. In this light, digital media include the finger as the original extension of the human body, the coin, the yad (“hand” or Torah pointer), the manicule (or “pointing hand,” “index,” or “digit” in the margins of eleventh to eighteenth-century typography), the piano keyboard, filing systems, the typewriter, and the electronic telegraph. All these media, among many others, are digital in the simple sense that humans interface with them digitally, or with our fingers via manual manipulation and push buttons. Fingers and digital media alike flip, handle, leave prints, press, scan, sign, type. The touchscreens we pet and caress today continue the age-old work of counting, pointing out, and manipulating the literate lines animating every modern media age, including our own. Digital media, such as these, point and refer to real-world objects outside of themselves, and this transducing from the symbolic to the real limits both the computing and the indexing power of digital media.

[…]

Both analog and digital techniques, in other words, index the real approximately—and they do so differently and they do so nonexclusively. (There are many other kinds of media.) To imagine the opposite—that digital and analog are in exclusive opposition—is unthinkable: first, imagine that digital media and analog media were in fact the only ways of representing the world. Now suppose somehow there were a total convergence between digital computing and the real world (imagine your smartphone contained the whole world precisely). Even were this to somehow be the case, the end relationship between the digital profiles of the contacts in your phone and the real-world people you know, or between the symbolic and the real, would be—as it always has been—indexical, not computational.

[…]

Digits, like fingers, can wag, curl, clench, and deliver crushing blows. The spread of digital computing is no unmitigated good for all, and especially for the disenfranchised many. As Langdon Winner predicted decades ago, the larger the franchise, the more computing power stands ready to serve its interests. Whatever else big data may mean, big data surely means big data brokers. Digital media index not only our world but all known possible worlds— and this means, in practice, those parts of the world that many would prefer not to consider. The cascading collapse of privacy is not only a sweeping narrative of decline—it demotes the status of the modern individual to one on par with most humans in history: we are all again exposed to the elements and subject to powers far greater than ourselves.

[…]

Digital media have been counting the symbolic, pointing toward the real, and manipulating lives since humanoids have had fingers, even though the explosion of computing power has swept up the digital to such a degree that the techniques may now be outrunning the term. We can now count down the numbered days of the keyword digital, to rehearse Stoppard’s jest. To understand our digital age, we must understand not only the numbers—that digits count, compute, construct, and copy internally discrete symbolic worlds—but that digital media can point to or index all possible worlds, not only our real one. This second point helps counterweight, sober, and caution Whiggish enthusiasm for the ongoing digital revolution leading to total media convergence or a technologically determined single future.

The work of digital media can be said to rest at our fingertips. The work of digital computing is similar to counting on our fingers: we think counting is abstract and without obvious real-world unit, and yet counting takes place on the very handy extensions of ourselves—digits, media, and their combination—that permit our bodies to interact with and to manipulate a material world. The human species has always already been born digital: building tools that count, index, and manipulate the world is almost unique to the anthropoid species—those higher primates with digital tools built right into their hands. While counting 1 + 1 = 2 on our fingers is computationally exact, to do so is to engage in higher abstraction: without a unit or referent, the number “2” remains a quantity without qualities in the real world. Only by indexing our counting to real-world objects do we embody our computational abstractions. Human hands, in other words, are the first digital medium to don real-world units that apply with probabilistic, and never precise, degrees to all possible worlds around us. By pointing or orienting ourselves to different objects, our digits have long manipulated the world around us. This is nothing new: what is new is the commanding degree and scale to which, in the past seventy years or so, trivially large reservoirs of computing power have begun to be consolidated in the hands of increasingly powerful data-rich institutions—corporation and state alike—and much less so selforganizing groups of people. Socioeconomic privilege continues to scale with digital privileges. (The belief in sousveillance as a viable way of resisting institutional surveillance is most concentrated among affluent technoactivists.)

These trends suggest that the consequences of computational power itself will not converge, and there is no reason to imagine that the institutions that command its powers will (want them to) either. Rather the far more awesome power resting in the hands of our digital species is to point to and manipulate any number of modeled worlds. There remains much to be done to model more equitable and sustainable worlds. Perhaps we can begin by understanding the digit as an openly imitable and probabilistically imperfect index of any thinkable world, including this world, with which there can be no final convergence. The last seventy years have ushered into existence a host of digital devices that now populate our pockets, warehouses, and working models of the world. The lot of these reality doppelgängers, like that of all indexical media before them, is to point to endless and imprecise imitations of their makers.

Excerpts from Peters, B. (2016). Digital. In B. Peters (Ed.), Digital Keywords: A Vocabulary of Information Society & Culture (pp. 93–108). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

.m

.crum

InstaFood, a simulacrum

Critiquing popular culture made easy

With sighs of “What kind of world do we live in”

Noodles on Instagram appear to matter more than instant noodles

Visual representation more attractive than the food itself

The image more irresistibly delicious

than the scrumptious bite bursting with flavour, texture, aroma

Performance of eating more important than nourishment

Are we this disconnected from our food?

Scoff

Criticize

Dismiss

Or

Like

Share

Forward

What if our souls

our hearts, however dark and small,

are nourished in this way

What if such things connect us to one another more mightily than chewing connects us to food?

If our detachment from food is dwarfed by our sense of detachment from others,

our craving for human connection stronger and more urgent than our bodily appetites?

Who am I to judge?

…

InstaFood, a simulacrum

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

24 in x 18 in

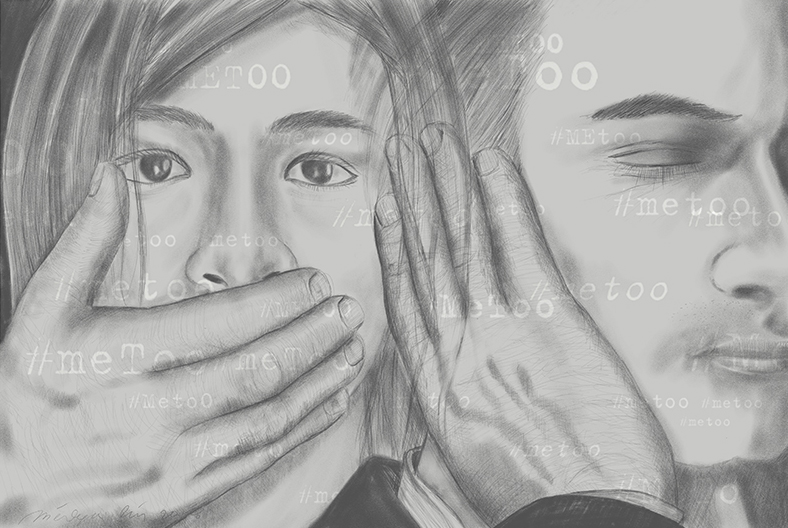

Hashtagged

She almost lost her way,

Torn between a boundless zest for life

And an earth confined by layers of gas

Ritualized by a performative digital mass.

She wanted to live a radical dream

A far-reaching imagination

With joyful leaps

And vast horizons………

But the village would never give heed.

She read Foucault with enthusiasm

Decided to disturb that ubiquitous power

To knock down this insidious discourse

And these panoptical towers

To make her own history

To fabricate victory

And reinvent the wheel of power.

But after all,

She was that clumsy girl

Who was as aloof as an urbanite

With a nomad’s spirit roaming loose at night

Who danced with goliaths

And hashtagged #cat #triumph and #defiance.

…

Hashtagged

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

Thirsty

Haus

Zaman yang menderu-deru, bagaikan napas seekor naga, sudah tiba. Orang sejagad haus percik api sang naga. Dialah yang membuatmu berseri bagai bunga disinari rembulan.

Percik api itu diburu, sekuat tenaga, meski tak jarang apinya membakar diri sendiri.

Percik api itu, like, love, share, serupa candu dahsyat. Begitu kau mencicip, kau tak akan bisa berhenti. Seperti air segara, dia tak bisa menjawab hausmu. Kau akan minum, lagi dan lagi.

Percik api itu, like, love, share, serupa mata panah. Kesaktiannya bisa membawa cinta dan daya hidup.

Tapi, dia juga membawa batu kerikil prasangka dan dengki yang bekerak, dengan atau tanpa alasan. Yang tanpa ragu membakar desa dan kota yang jauh.

Thirsty

The roaring epoch, like the breath of a dragon, has arrived. People of the universe are thirsty for the dragon’s fiery spark. It is the one who makes you glow like a flower under the moonlight.

That fiery spark is hunted, with might and main, even though it frequently burns itself.

That fiery spark, like, love, share, resembling a fierce opium. Once you taste, you won’t be able to stop. Like ocean water, it can’t quench your thirst. You will drink, again and again.

That fiery spark, like, love, share, resembling an arrowhead. Its magic can bring love and vivacity.

But, it also carries pebbles of bigotry and encrusted begrudge, with or without reason. Without hesitation, it sets fire in faraway villages and cities.

(English translation by Merlyna Lim)

…

Thirsty

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

18 in x 24 in

Time

The great British poet John Keats, dying of consumption, left behind an odd, unrhymed fragment. It is so intimate, so incarnate, that many have thought it must be addressed to a lover, possibly his fiancée Frances (Fanny) Brawne.

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou would wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calm’d—see here it is—

I hold it towards you.

The living hand, so alive and “capable,” now held out in a gesture—of beckoning, welcome, caress, pleading?—would only terrify the reader out of their blood if it were to return later from the grave. The lack of punctuation adds to the interpretive possibilities. No period between “dry of blood” and “So,” for instance, almost suggests a kind of total blood transfusion, life traded for death. But the speaker is not yet dead and is preserved forever thus in the timelessness—timefulness—of the poem.

The poem and the image both teach the impossibility of living by the rule of “carpe diem.” The day is too fast to grab, the last breath too urgent to punctuate. The hand that tries to gather it, though capable of earnest grasping, can only let it go. See here it is—I hold it toward you.

…

Time

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

Knitted,DNA

how they wish to find the genes that explain everything

how they wish to find the genes that deliver simple causalities

how they wish to forget the fear that nothing is certain

how they wish to forget the consequences of their choices

how they wish for us to believe that our destiny is engraved in our genes

how they fear for us to believe that we are knitting our destiny.

we are open biochemical systems

in constant exchange with the world

…

Knitted, DNA

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

Liked

Elle se regarde au lieu de vous regarder, donc elle ne vous connaît pas.

Pendant les deux ou trois accès d’amour qu’elle s’est donnés en votre faveur, à grand effort d’imagination, elle voyait en vous le héros qu’elle avait rêvé, et non pas ce que vous êtes réellement.

She looks at herself instead of looking at you, and so doesn’t know you.

During the two or three little outbursts of passion she has allowed herself in your favor, she has, by a great effort of imagination, seen in you the hero of her dreams, and not yourself as you really are.

from Le Rouge et le Noir, 1830 (Page 401, 1953 Penguin Edition, trans. Margaret R.B. Shaw).

…

Liked

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

18 in x 24 in

.

.

Carbon Mediation

Can you see the carbon?

Hands, match, earth. Representations composed of carbon, carbon inscribed upon carbon. A pencil of terrestrial carbon, paper of aerial carbon, carbon iterating carbon. You knew trees were made of air, of aerial carbon, but democracies are made of carbon too. You can see the carbon.

Can you see the politics?

…

Carbon Mediation

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

24 in x 18 in

Muted

Do you see me?

Hear me, perhaps?

Or my eyes only,

Or just the dancing of my hands

But the two numbers have changed us! You say,

Are we indeed a friend once was happy and play

All I know now I am busy talking throwing words

Disregarding the morning singing of flying birds

I have memory lost in the details of binary

And as your hands have muted my one soul in me

I forgot to pick up the ringing of your

zero indefinite humanly beauty

…

Muted

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

30 in x 20 in

Fragile Identity

Lucius una quidem, geminis sed dissita punctis

littera; praenomen sic nota sola facit.

post M incisum est. puto sic, non tota videtur;

dissiluit saxi fragmine laesus apex.

nec quisquam, Marius seu Marcius anne Metellus

hic iaceat, certis noverit indiciis.

truncatis convulsa iacent elementa figuris,

omnia confusis interiere notis.

miremur periisse homines? monumenta fatiscunt,

mors etiam saxis nominibusque venit.

Lucius is indeed one letter, but it is separated off by two points—that is how a single letter makes a praenomen. After it an ‘M’ is cut—at least I think it is, but it is not wholly clear; its top has been damaged and rent asunder by a break in the stone. Nor can anyone know for certain whether it is a Marius, Marcius or Metellus who lies here. The shapes of the letters lie mangled, their forms decapitated; all have perished in the confusion of marks. Are we to wonder that men have died? Tombstones decay, death comes even to stones and the names on them.

Epigram 37. 1–10

…

Fragile Identity

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

Love

Two different hands

One heart

Two different worlds

One vision

To keep working with each other

To shape something meaningful together

To see possibilities for the future

To love and to be loved

…

Love

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

24 in x 18 in

Hand Game

What is Rock-Paper-Scissors-Gun?

It is a hand game that is easy, quick, and addictive for many individuals of all ages. It is popular in some countries, notably in the United States of America.

How to play it?

To make Rock, make a fist. For Paper, hold your hand out flat. For Scissors, spread your middle and index fingers. For Gun, extend your thumb and index finger.

If players make the same gesture, the game goes on. If not, the winner is decided by a harmonic and intransitive method.

Rock crushes Scissors; Scissors cuts Paper; Paper covers Rock; Gun kills Paper; Gun kills Scissors; Gun Kills Rocks; Gun kills Player 1; Gun kills Player 2; Gun kills Player 3; Gun kills; Gun kills; Gun kills; Kills; BANG BANG BANG!

…

Hand Game

2018

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

30 in x 20 in

In Tune

Music

When music sounds, gone is the earth I know,

And all her lovely things even lovelier grow;

Her flowers in vision flame, her forest trees

Lift burdened branches, stilled with ecstasies.

When music sounds, out of the water rise

Naiads whose beauty dims my waking eyes,

Rapt in strange dreams burns each enchanted face,

With solemn echoing stirs their dwelling-place.

When music sounds, all that I was I am

Ere to this haunt of brooding dust I came;

And from Time’s woods break into distant song

The swift-winged hours, as I hasten along.

(From Georgian Poetry, 1913–15, edited by Sir Edward Howard Marsh).

…

In Tune

2019, for James

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

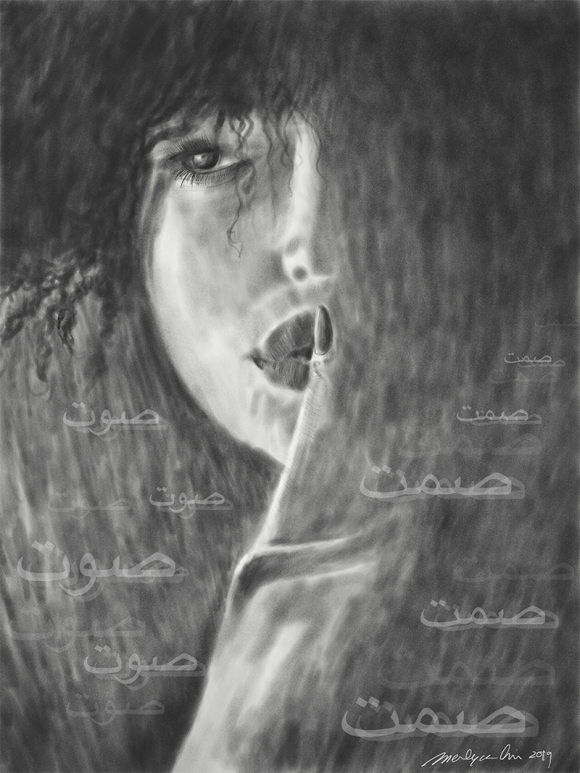

Sound/Silence

We all have dreams (a song)

remember.

sand grain in mouth.

wind that beckons against us.

that silence. which was full of sound.

secrets found within books

our hearts that respond to the rhythm of our feet.

we all have dream.

but we can’t all remember them.

mountains. sky that runs for miles and miles.

desert.

that certain loneliness that sits inside of you

like a pearl.

like the paintings on walls. faceless yet spoken.

in our most secret places, we build our relics.

we collect them

and pile them. to remember ourselves by.

to remember something.

(we all have dreams)

…

Sound/Silence

2019

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

18 in x 24 in

Consume

Hey, that looks good.

I’ll have a bite.

[nibble]

Mmm, this is good!

I’ll have some more.

[munch munch]

Oh yeah. More please.

Er, maybe that’s enough?

No, gimme gimme.

[CHOMP]

But others…

I want MORE! For ME!

[ ]

When is enough, enough?

…

Consume

2018

Graphite pencil on paper

18 in x 24 in

Walk

Cities are increasingly upheld as powerful global actors—sites of focused cultural engagement, centres of significant economic and political power, and home to expanding, diverse communities. The cityscape portrayed in Walk, brings the current import of cities and their global dynamics to the fore. This drawing depicts the fingers of a hand playfully traversing the tops of gleaming skyscrapers. The walk is set against a curtain of delicately rendered data, language, and information, which flows vertically as it disappears into the horizon. Walk raises questions about how digital technology mediates our everyday engagement with and exploration of urban space. We understand and consume cities through readily available data, regardless of geographic proximity.

Lim’s walking fingers can be read as a lighthearted reference to the 19th century flâneur,who, according to visual culture scholar Nicholas Mirzoeff (2016), offered a new means of looking at the city in the modern era. Key to the flâneur’s power was their ability to view while rendering themselves invisible—“seeing without being seen” (p.166). Following this thinking, it seems fruitful to consider Lim’s drawing in relation to Wendy Chun’s (1998) “gawker,” a user that similarly navigates cyberspace as a spectator, maintaining their invisibility. Of course, as Chun points out, users are very much visible within the digital realm. Calling to mind these tropes, Walk underscores the complicated dynamics of visual consumption, invisibility, and power, all through a light-hearted and surreal depiction of a stroll.

…

Walk

2019

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

18 in x 24 in

Mending (A Broken Heart)

My heart is a grain

Dear heart, why are you so selfish?

Why do you love the enemy in vain?

Why do you seek faith from the unfaithful?

Why do you strike iron that is cold?

And you, whose cheeks are like the lily,

The lily is jealous of your beauty.

Go down this dead-end street just once,

You’ll light a fire under its residents.

My heart is a grain, your love, a mountain.

Why crush the grain under the mountain?

Forgive me dear boy, forgive me.

Don’t needlessly kill a lover like me.

Come now, take a look at Rudaki,

If you want to see a lifeless body walk.

…

Mending (A Broken Heart)

2019

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

24 in x 18 in

.

.

Untitled

Darkness, for her, is real; everything else is an illusion

She feels, grasps, and is touched by the dark

She embraces it; for once, the dark is her only true friend

But even in the quiet of the darkest dark

The light whispers in the unheard voice

Through the crack, cracks in everything Cohen says, the light slips in

Through her wound, Rumi once says, the light finds a way to enter her

It gleams, it glows, it reveals

The light brings out the colour of the dark

It paints a colourful portrait of her life.

…

Untitled

2019

Graphite and digital pencils on paper

18 in x 24 in

Biographies

Contributors

A habitual trifler and a victim of what he called “the poetic itch”, AUSONIUS (Decimius Magnus Ausonius) was a 4th century Gallo-Roman poet, rhetorician, and consul from Burdigala, the modern Bordeaux (France), in Aquitaine.

GHADAH ALRASHEED is Interim co-Director of ALiGN Media Lab and Postdoctoral Fellow at Carleton University.

An experienced media executive based in Jakarta, RINI ANDRIJANI always be a keen observer on how media affects people’s daily life; especially nowadays, when online information has made an “egalitarian” world for all.

A political science and media scholar based in Berlin, (Dr) ANNA ANTONAKIS investigates intersectional-feminist perspectives in International Relations and technology studies.

As a marketing researcher, ANTI ANTONO studies consumer habits, choices and motivations. She finds getting rid of things she doesn’t need profoundly liberating.

SARA BANNERMAN is no longer on Facebook.

RENA BIVENS studies how software programs our identity, prefers defence when she’s on the soccer pitch, and has never been a fan of potlucks.

MARDIYAH CHAMIN, journalist, worked with Tempo News Magazine, former Director of Tempo Institute, traveler and storyteller. She is a founder of PuanIndonesia.com, a platform of collection of Indonesia women stories.

WALTER DE LA MARE was an English poet, short story writer, and novelist. Having lived an ‘outwardly uneventful’ life, de la Mare is considered one of modern literature’s chief exemplars of the romantic imagination.

HANNAH DICK is an Assistant Professor in Communication and Media Studies. Her work brings together media studies with the study of religion.

A journalist and author, KATHY DOBSON studies datafication and media in/for marginalized communities. She is a PhD (ABD) candidate in Communication and Media studies and Interim co-Director of ALiGN Media Lab at Carleton University.

Granddaughter of ordinary farmers with extraordinary love for their homelands, Indigenous researcher ELIZABETH SUMIDA HUAMAN works to fulfil her ancestors’ visions for a beautiful world.

DEWI HUTABARAT lives in Indonesia; a lifetime learner dream of the world with no hunger, with equality and peace. She likes the challenge of cooperative economy.

KARIM H. KARIM is seeking to be.

Imported from the non-allied parts of Europe, IRENA KNEZEVIC is a devotee of delectable and auditory pleasures, including dumplings and the voice of Ira Glass.

AMANDA LAGERKVIST, PhD is a founder of existential media studies and an Associate Professor of Media and Communication Studies at Uppsala University, Sweden.

TRACEY LAURIAULT is a fighter for open data and evidence-based policy. She is an Assistant Professor of Critical Media and Big Data at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada.

Based in Singapore, RITA PADAWANGI is a humanist, mother, woman, observer, researcher, scholar, student, teacher, writer, organist, and occasional sketcher who likes to eat and travel.

BENJAMIN PETERS is Hazel Rogers Associate Professor and Chair of Media Studies at the University of Tulsa. His hands are busy with books, kids, and Ultimate Frisbee.

JOHN DURHAM PETERS teaches at Yale, likes Canadian media theory, the poetry of Emily Dickinson, and tossing Frisbees.

CAROLYN RAMZY is an ethnomusicologist and an Associate Professor of Music at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada.

SANDRA ROBINSON is a communication and media studies scholar based in Ottawa. She finds there are too few hours in the day to run, shred guitar, and chase algorithms.

A talented singer and instrumentalist, RUDAKI (Abū ‘Abd Allāh Ja’far ibn Muḥammad al-Rūdhakī) was a 9th century Persian poet regarded as the father of Modern Persian literature. His life ended in a wretched poverty.

CHRIS RUSSILL is a carbon-based, carbon-emitting life form residing in the unceded lands of the Algonquin nation.

L. AYU SARASWATI is Associate Professor and Chair of Women’s Studies department at the University of Hawaii, Manoa.

For 30 years, DAN SAREWITZ has fruitlessly tried to demystify the role of science in politics to keep the two from destroying each other.

ABIDAH SETYOWATI is a human-environment geographer currently based in Canberra (Australia). She loves traveling despite getting lost everywhere she goes.

SARAH E. K. SMITH is a writer and independent curator based in Ottawa. She is an Assistant Professor in Communication & Media Studies at Carleton University.

A major author and minor bureaucrat, STENDHAL (Marie-Henri Beyle) was a 19th century French writer. His writing helped mark the advent of both romanticism and realism in French literature.

CARMEN WARNER is a PhD student in Communication at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada.

LIAM COLE YOUNG is Assistant Professor of Communication and Media Studies at Carleton University and the author of List Cultures: Knowledge and Poetics from Mesopotamia to BuzzFeed.

Trained as a Molecular Biologist, JAMIE ZULAUF changed their perspective on health, now working as an M.D. for Child & Adolescent Psychiatry in Berlin, Germany.

Graphic designer

KIT CHOKLY studies, creates, and lives through digital media. Still, they find few greater joys than the sensory experiences of sharp pencils, used bookstores, and print shops.